Pop quiz: Entering Wednesday night, which Royals batter had the highest average exit velocity on the team this season, according to Statcast? Before you answer, go back in time to a point before you read the title to this article, because otherwise you’re cheating. Now, who’s your guess?

Eric Hosmer? Nope, he’s in second place.

Lorenzo Cain? He’s in eighth.

Salvador Perez? Also incorrect, as he’s in sixth.

You’re really bad at this guessing thing, aren’t you! Fine, I’ll help you out. The answer, of course, is none other than Whit Merrifield.

The 27-year old rookie has an average exit velocity of 93.8 mph this year. Among the 374 batters with at least 25 batted balls recorded in 2016, that ranks 17th, just behind Joc Pederson, and just ahead of Josh Donaldson and Miguel Cabrera. Just as everyone expected, Merrifield is hitting the ball as hard as MVP Award-winners.

Since some Statcast data has become publicly available, exit velocity has been all the rage, although it can be given far too much weight in some circles. A 100-mph grounder isn’t going to fall for a hit as often as a 100-mph line drive, for example. Launch angle matters.

So let’s look at the Royals’ launch angle leaderboard, and we see that Merrifield is not at the top. Aha! Like I’ve been saying, all these new-fangled statistics are liars. Except, well, Merrifield may not be at the top, but he’s near it, tied for fourth, with Mike Moustakas at 14 degrees. Among all batters in the previous link, that angle is in the 70th percentile. Not in the elite category, but easily above average.

This tells us Merrifield isn’t simply hitting the ball off the plate in every at-bat. He’s getting the ball in the air more than half the time, including a line drive rate of 30.6 percent, which puts him in the 86th percentile of AL batters with at least 40 plate appearances. He is hitting some ground balls (44.4 percent ground ball rate) but even his grounders are averaging 92.4 mph off the bat, with a launch angle of just -2 degrees. His ground balls have traveled an average of more than 155 feet, which is the second-highest average distance among all batters with at least 10 grounders recorded. In other words, his ground balls are still being hit hard, and they aren’t going directly down.

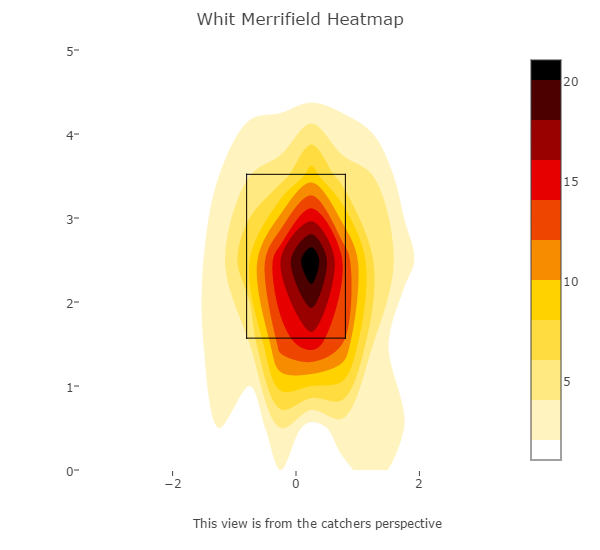

Merrifield is hitting the ball hard, even on ground balls, so it doesn’t take a rocket surgeon to see how he’s been able to have so much success thus far. His BABIP may be elevated, but it’s not due to a bunch of duck snorts and flares. His excellent results have been a result of excellent contact. But part of that success has also been a result of pitchers not attacking him like a successful major-league hitter. Take a look at all of the pitches Merrifield has seen this season.

Obviously there are a handful of pitches down and away from him, but clearly big-league pitchers have not shied away from going after Merrifield. He’s seen a fastball more than 63 percent of the time, and while that isn’t close to the league lead, it does provide more support to the idea that guys are being aggressive against him.

Granted, Merrifield hasn’t shown an elite eye at the plate, swinging at a few too many pitches out of the zone, but he’s seeing enough strikes that his current 0.0 percent walk rate kind of makes sense. And if we’re being honest, filling up the zone against a guy like Merrifield, based on his history, probably isn’t a bad idea. He’s never shown a ton of power potential, and with his speed, it’s not worth the risk to throw a bunch of junk if he ends up with a free base. So I get it.

However, one of Merrifield’s best skills is his ability to control the strike zone. He has a short, compact swing that keeps the bat in the zone for a very long time, which maximizes his contact ability. It was one of the first things that stood out to me when I saw him in Omaha a couple of years ago. That 170-pound (if that) second baseman didn’t have much pop, but the swing path was exactly what you’d like to see from a player of that build.

His contact skills have continued at the big-league level, as he’s making contact on more than 91 percent of his swings at pitches in the zone, trailing only Jarrod Dyson among Royals. If a pitcher is willing to throw a strike to Merrifield, there’s a good chance the ball is going to be put in play. Prior to this season, those balls in play would likely not be hit with much authority, but because of Merrifield’s offseason diet and workout regimen, he’s added enough muscle to do more damage on batted balls. He’s probably not going to hit double-digit home runs, but all those line drives can lead to oodles of doubles and triples in the spacious Kauffman Stadium outfield.

We’re now roughly 750 words into this article and I’ve yet to mention that Merrifield has all of 45 major-league plate appearances, and only alluded to his .444 BABIP. I do think Merrifield’s skillset will allow him to post an above-average BABIP, but still, the sample is small, and some regression is likely coming. Just because he’s earned a high BABIP so far doesn’t mean it’s sustainable over a long period of time.

Pitchers will eventually stop serving up fastballs in the middle of the zone. Or, at least, they should stop doing that, if they want to keep him off the bases a bit more often. Once the pitchers adjust, it will be up to Merrifield to make his own adjustment.

If he can learn to lay off more pitches out of the zone, any BABIP regression could be partially offset by an increase in walks, and if he can prove to be a weapon on the basepaths, that could lead to him seeing more pitches in the strike zone, which once again feeds into his biggest asset.

Had you asked me two years ago what Merrifield’s future would be, I would’ve said he’d basically be organizational filler. I still don’t think he’ll be Ben Zobrist, or a poor man’s Ben Zobrist, and he may not even be a regular starter in the next few years. However, his physical transformation has allowed his strengths to shine brighter than they could before, and the league has yet to recognize it. He’s making a big impact at the moment. If and when that recognition surfaces, Merrifield’s impact could certainly be lessened. But for now, the Royals have a valuable bat near the top of the order, even if it’s one no one could have expected just three months ago.

1 comment on “Explaining Whit Merrifield’s Early Magnificence”

Comments are closed.