Joakim Soria didn’t get off the kind of start he was hoping for this season. He allowed four runs in his first three appearances, and his ERA after seven innings of work was an unsightly 7.71. Fifteen batters reached base against him in that span. His return to the K looked anything but special.

It was at that point that noted wizard and Royals pitching coach Dave Eiland made a suggestion. He noticed Soria had been drifting open with his front side too much, so they made a slight tweak to ensure he remained up and down instead of going side to side. As Jesse Newell noted following Soria’s appearance on April 20, the adjustment seemed to make a difference right away, particularly with the movement on Soria’s slider. But his slider may not have been the only pitch improved by the adjustment.

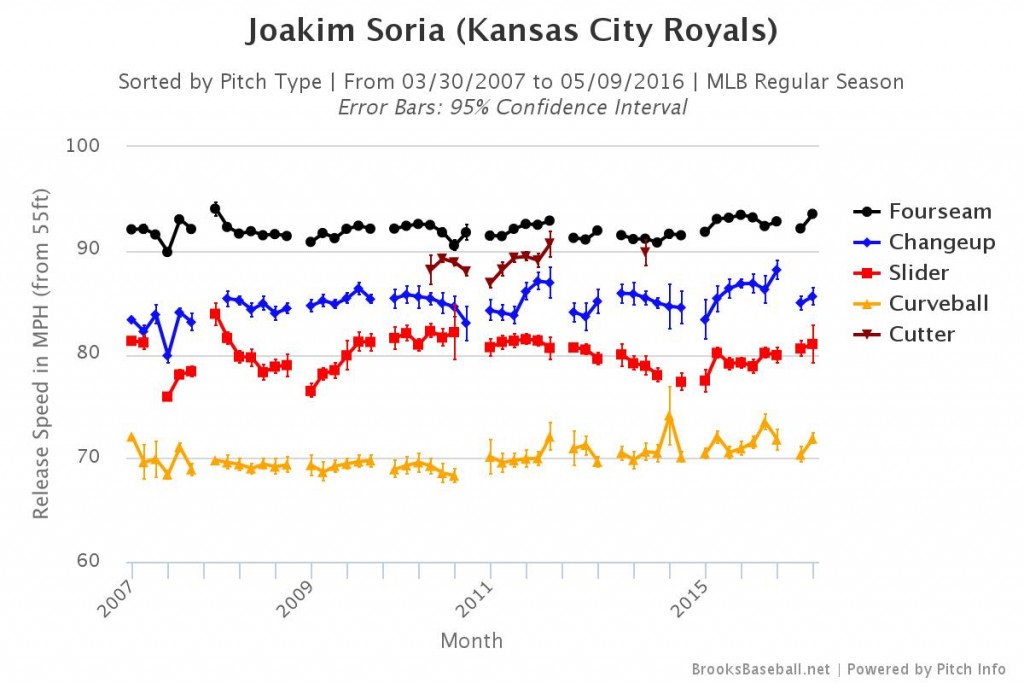

If you’re familiar with Soria’s career, you likely know he’s never been a high-velocity guy. He’s been an excellent closer because he can command his four pitches to all parts of the strike zone, and despite a lack of premium petroleum with his fastball, his stuff was more than good enough to miss bats. Here’s a look at Soria’s velocity throughout his career:

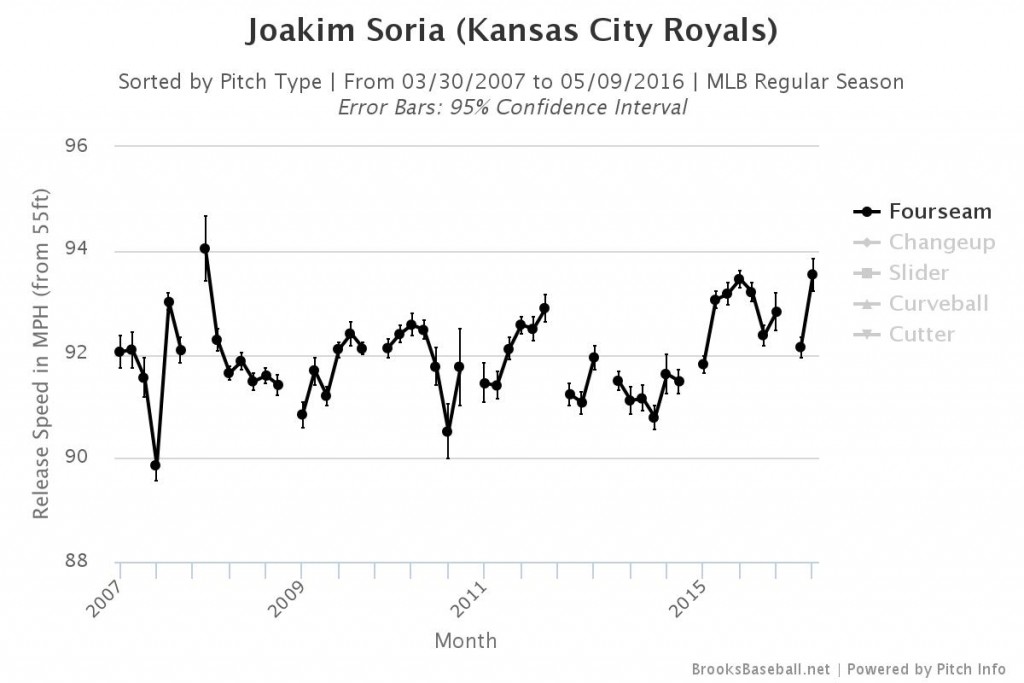

That’s a little difficult to spot differences because of the wide range in speeds, so let’s only focus on his average fastball velocity:

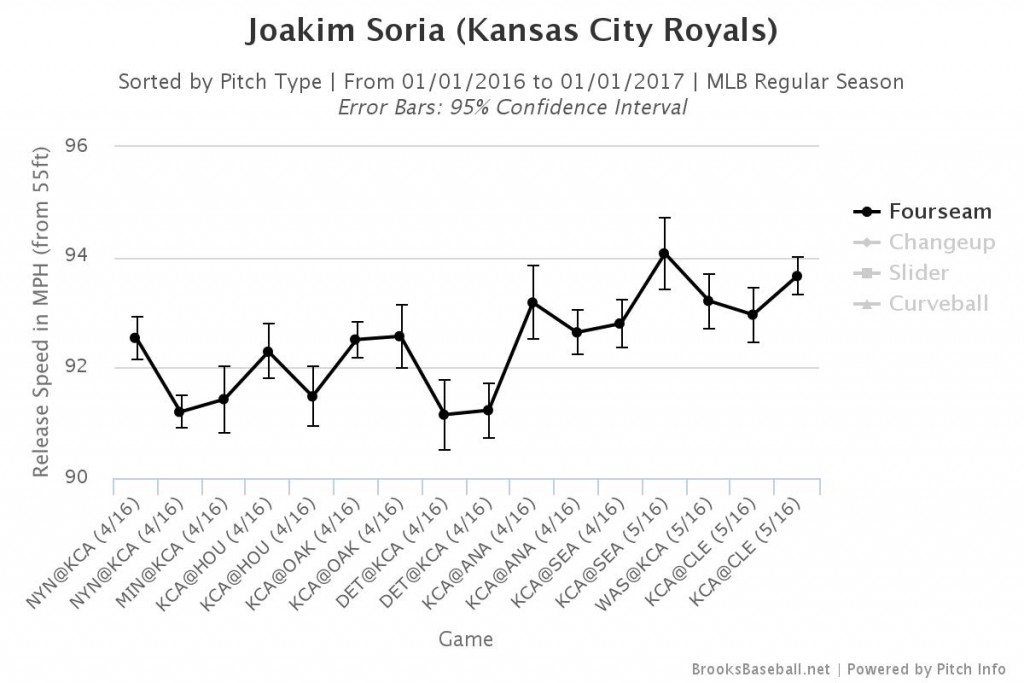

You’ll notice that last data point is only topped by one other month in his career, in 2008. Finally, one more graph, showing Soria’s average fastball velocity by game in 2016:

The mechanical adjustment was made prior to his second game against Detroit, and while there was no noticeable difference in that game, Soria’s velocity jumped up in the next series, and every one of his last seven appearances has seen a higher average velocity than any of his first eight appearances. His maximum velocity topped out north of 95 mph three times in the last seven games, a mark he bested just thirteen times all of last season.

It’s possible the increase in velocity is simply a result of a pitcher’s arm loosening up as the season progresses, as happens with many other pitchers. However, Soria’s current average fastball this month is sitting at 93.5 mph. If he maintains that for another three weeks, it would be the second-highest mark for any month in his career, trailing March of 2008, which consisted of a single inning of work. Even if he loses a bit of that, it does appear that Soria’s found some velocity that hasn’t been there for much of his career. In fact, Soria’s average velocity this year (92.5 mph) is only topped by last year’s mark of 92.8 mph. If the velocity is a result of a warming arm, it’s not unreasonable to think Soria could set a new career high.

Rarely in baseball is something caused by just one thing. In this case, it’s possible the higher velocity stems from Soria getting loose and from a mechanical alteration. With better mechanics, a pitcher may be able to do different things with the baseball, including but not limited to: throwing it harder. I’m not a physicist or a doctor or even a pitching expert, but it doesn’t take one to realize an athlete’s muscles are capable of doing more when they’re working in an efficient manner. By staying in line, it’s easier for Soria to finish his pitches all the way through, which might be giving his fastball a little more firepower.

Another way of looking at the adjustment, beyond the video in the linked article above, is by focusing on Soria’s release point. You can notice a change following that first game against the Tigers.

The change isn’t huge, but it’s there. When his front side was pulling off early, it was causing him to release the ball just a touch earlier than he probably wanted to, and throwing a pitcher’s timing off ever so slightly can have horrendous results. Now that he’s staying on time, it’s easier for him to get the ball where he’s wanting it to go, and he’s able to put a little more on the pitch.

Soria’s fastball sat at 92 mph prior to the tweak, and now, it’s sitting at 93 mph. The movement hasn’t changed much, but he’s throwing it for strikes more often, which allows him to use his secondary pitches, and those pitches are moving more since the adjustment. His changeup has more drop, his slider and curveball have more horizontal movement, and while it’s not drastic, it’s enough to miss barrels.

Since Eiland’s suggestion, Soria is allowing a line of .179/.281/.375, and the only earned run he allowed came on a home run from Mike Trout, which is a thing that happens sometimes when facing Mike Trout. He also allowed a pair of doubles, one to Johnny Giavotella on a play Jarrod Dyson probably could’ve handled better, and another to Ryan Zimmerman, who apparently used up all of his hits in Kansas City before heading to Chicago last weekend.

Obviously his .174 BABIP allowed during this stretch isn’t going to last all year, and while Soria has been lucky recently, he’s also been good. His improved command and stuff have led to more swings against three of his pitches, which includes more swings against his pitches that aren’t in the strike zone. Soria is actually allowing more contact since making the change, but all of that contact is on pitches out of the zone, and that’s the kind of contact the Royals are fine with allowing.

It won’t always be weak contact, but it’s more likely to be manageable contact than something that’s left in the middle of the plate after falling behind 3-1. In addition to inducing more chases, the poorly-hit balls in play are actually landing in gloves, so it’s a bit of a reversal of fortune from his early-season woes. It’s funny how those things usually even out.

Despite a terrible debut, Soria now looks very similar to the type of pitcher the Royals expected to see when they locked him up to a three-year deal this winter. And there are even some parts of his game that look better than they have in the past. While his average fastball velocity was higher last year, his secondary pitches are moving more this year. His numbers still haven’t fully recovered from his first few appearances, but Soria now seems poised to return to being a productive member of the Royals’ bullpen.